The 8th China Goes Global Conference (CGG 2014), Chinese Globalization Association (CGA).19-21 Aug. Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China.

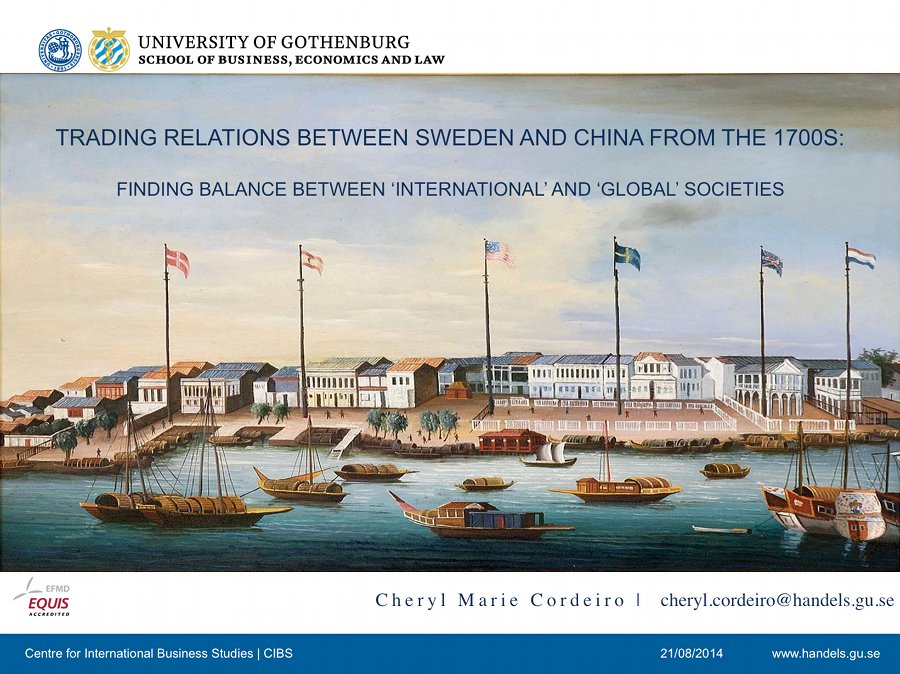

Trading relations between Sweden and China from the 1700s: Finding balance between ’International’ and ’Global’ Societies.

Abstract

As a reflection of east-west relationships in world history, tracing the processes of globalization, this article leverages conceptually, on the dual structure of world history, that highlights the differences between “international society” and “global society”. It uses the example of trade relations between Sweden and China from the time of the 1700s in illustration of a unique relationship between countries that have thus far seemed to find their own equilibrium of both being part of “international society” whilst having between themselves, a long term understanding of collaborating towards an envisaged “global society”.

Keywords: Sweden, China, global trade, 18th century, Swedish East India Company, globalization

In my last trip to Shanghai, in the past year, I had the opportunity to visit several universities in Shanghai city in an effort of research collaboration. And in one such meeting, I found myself seated at a table with my colleagues, where across the table, were seated a similar number of colleagues from the corresponding Shanghai university.

The question for discussion was – seeing that most of western academia has been built upon a broadly dichotomistic Aristotelian perspective, if there were an alternative paradigm of knowledge, what would that be built on?

I was fairly excited and I sat there actually waiting to hear from my Chinese colleauges if they could share something insightful from ancient Chinese philosophies that could contribute towards a new paradigm of academic thought or knowledge of the future. I was excited because I know some about Chinese history, where China in my view, has a lot of traditional knowledge to leverage upon today. But no, at the time, there was no particular idea of Chinese philosophies on academia for the future, but what ensued was an interesting discussion of possible collaborative research on that front.

And it is the very idea of collaboration in an increasingly global society that I would like to situate this presentation, highlighting what is special about Sweden’s trade history and trade relations with China for the context of today. And today’s context is that we’re at a point where the advancement in information communication technologies (ICTs) have really allowed us to get in touch with each other, covering great distances, in a much shorter time, thus resulting in many instances of juxtaposition of concurrent duo-world structures that can be described as:

[SLIDE 2]

International Society and Global Society

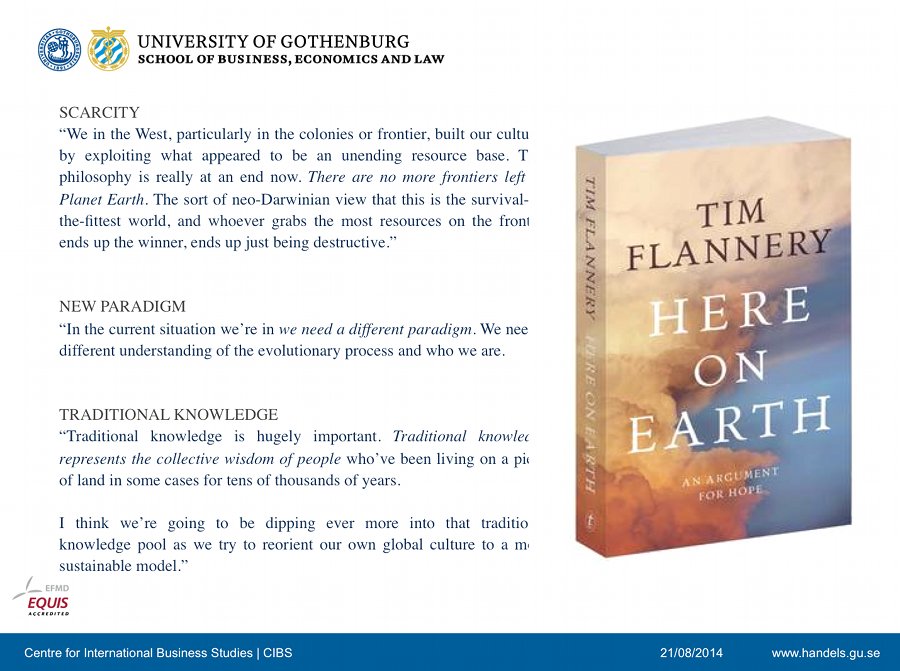

There are several voices in various scientific fields about this perspective. But a good argument for that the human species is approaching that point of a need for global integrative thinking and collaboration was put forth by a professor in paleontology, Tim Flannery. He has authored many books, one of which is entitled “Here on Earth”, published in 2010.

The main point of contention being that what we see now is this:

[SLIDE 3]

You’ll recognise this picture nothing questionable about it. The globe is divided into many sovereign states, under which many national and regional policies are created, that in turn reflect this world perspective, of many countries, many flags, division of territories, people, culture, beliefs, value systems.

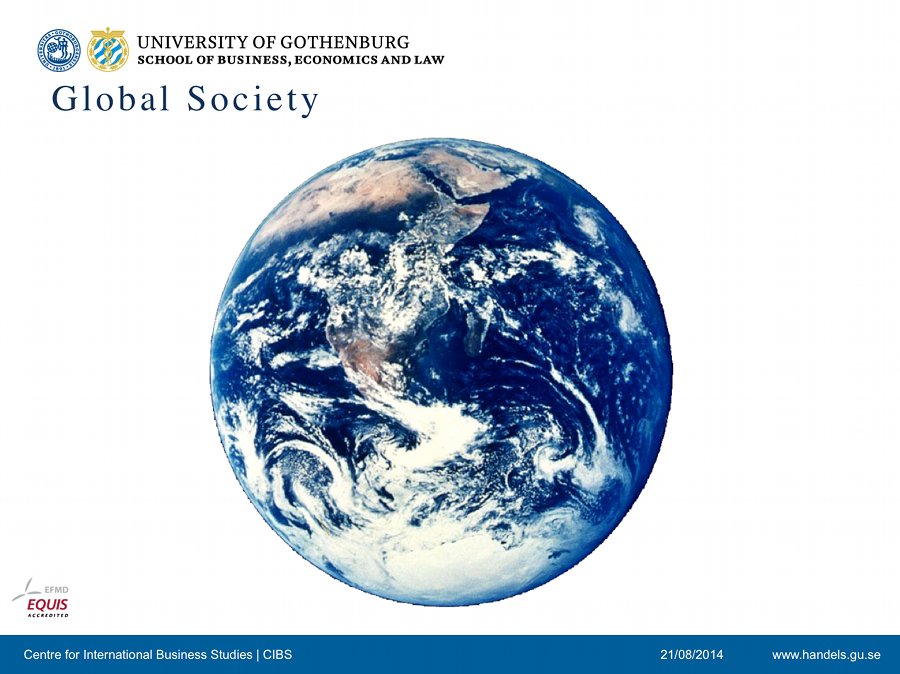

But if we took a step back, to view things from a slightly higher perspective, what we really have in this:

[SLIDE 4]

What we have is just one over-arching system, that within it, encompasses, many systems.

So how come it is that it is difficult to see this One system that encompasses many systems?

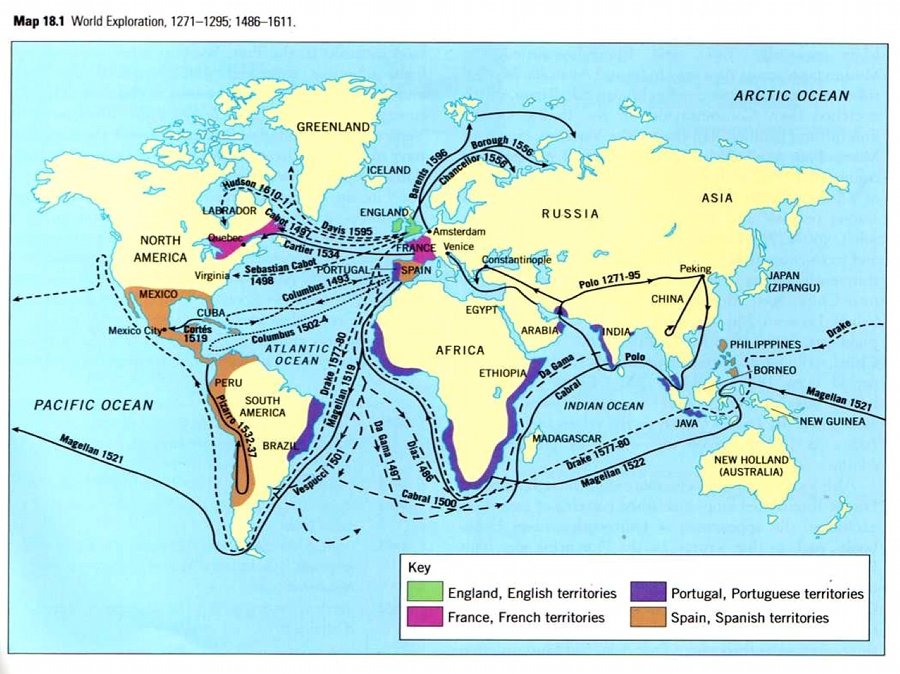

Perhaps the answer lies in that even in the first waves of globalization and early world trade, it was the conflation or the confusion between “one system” and “one system that contained within it, many other systems” that you witness here:

[SLIDE 5]

This is a World Exploration map from the 1200s and then from the 14 to 1600s.

It shows how different countries have colonized other parts of the globe outside of their own national boundaries. The British East India Company that colonized Singapore for example, had the mandate to act on behalf of the sovereign power, making it in effect, not just a trading vessel but one that had both British law and military backing, a mobile country that had the mission to colonize, Singapore being one such colony founded in the 1819.

[SLIDE 6]

Tim Flannery, whom I cite here as just one example of several voices in various academic fields on why it is that a global perspective is needed rather than an international perspective. The earth’s resources are finite and there needs to be a way for us to manage this limited resources between ourselves.

The idea of the survival of the fittest, is ultimately a destructive and self-imploding concept if taken to a pathological extreme.

With advancing ICTs, what becomes more and more a pressing challenge is precisely to know how to navigate the fine balance between international society and global society, towards a sustained future.

So there needs to be a new paradigm to come into order.

But where can / does that new paradigm come from?

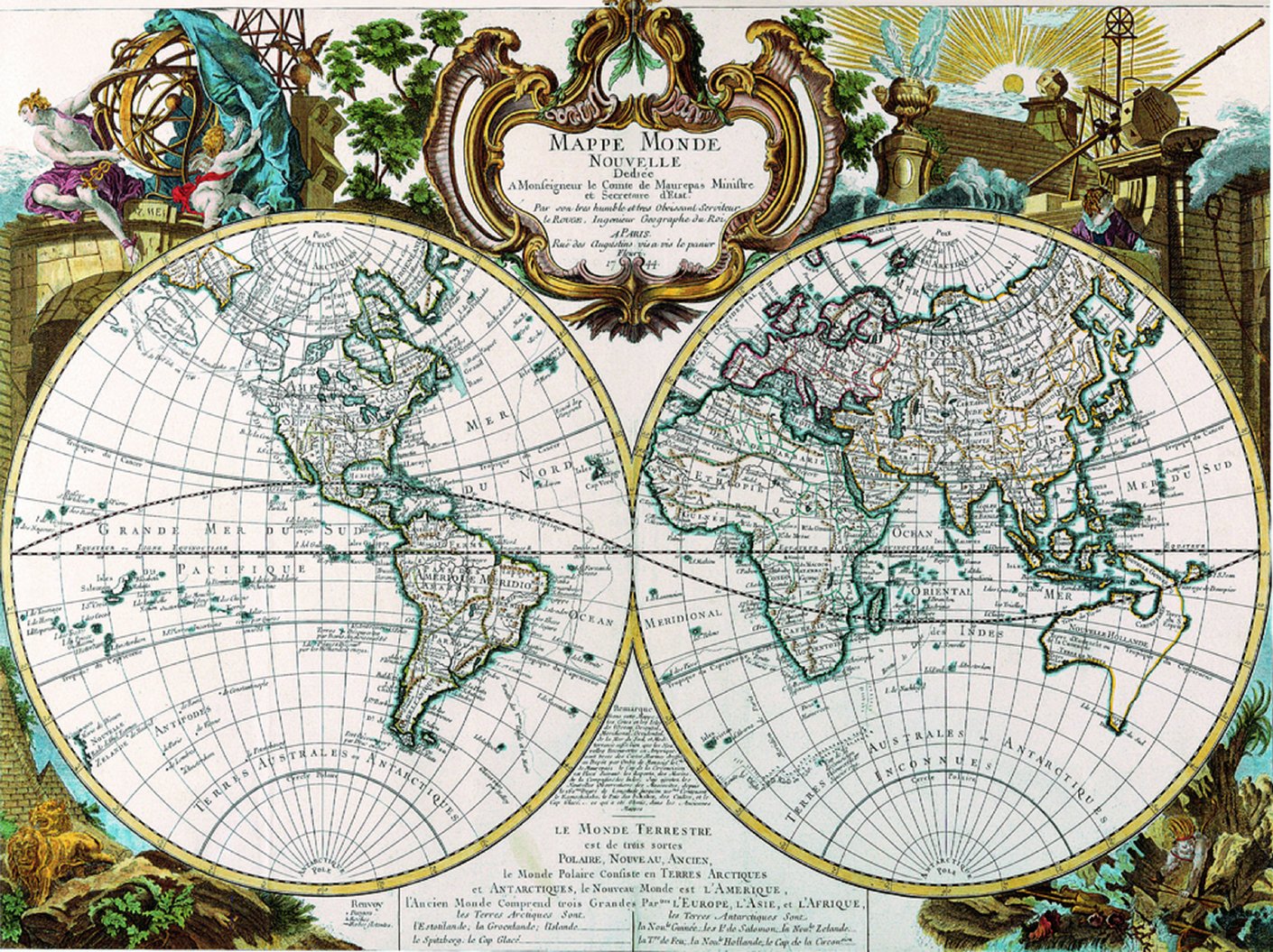

[SLIDE 7] (map of world from Rococo period)

Traditional knowledge. It is that which Flannery defines as the collective wisdom of people who have been living on a piece of land for tens of thousands of years.

To that extent then it could be argued that both the Chinese and the Nordic people share a common heritage of both being ancient civilisations who met in the 1700s as a result of the Swedish East India voyages from Gothenburg to Canton. As result of a desire for world trade. And this is what the world map looked like back in then, during the Rococo period.

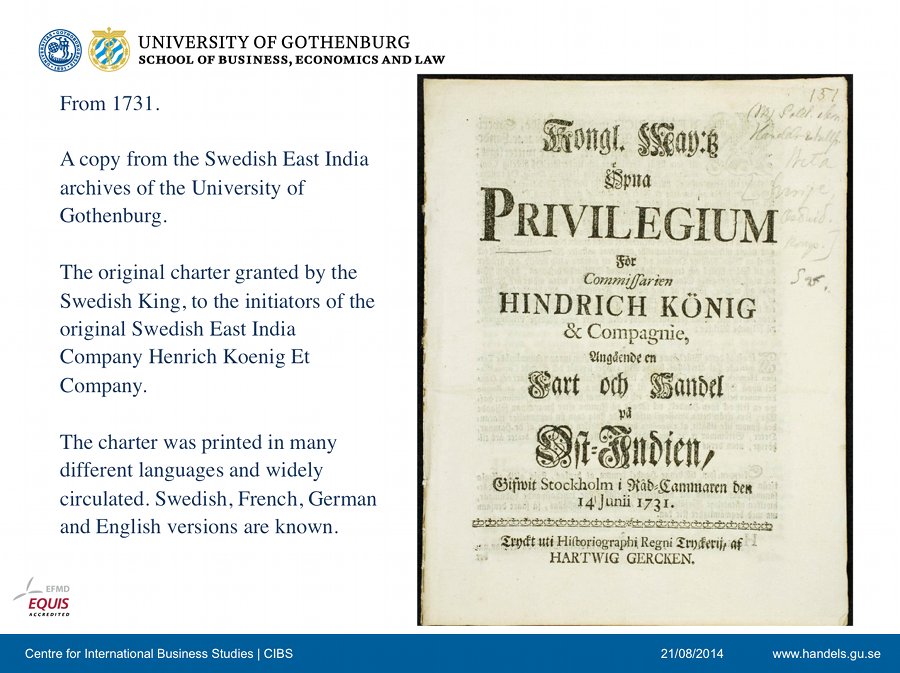

[SLIDE 8] (SOIC original charter]

This is a picture from the Swedish East India archives at the University of Gothenburg from 1731 – the original charter granted by the Swedish King, to the initiators of the original Swedish East India Company Henrich Koenig Et Company. It was printed in many different languages and widely circulated. Swedish, French, German and English versions are known.

The relationship between Sweden and China could a large extent be said to be based upon asymmetrical socio and political influences.

To the Chinese, Sweden is one among 42 other European countries, perhaps known as the country that gives out the Nobel Prizes and some might have heard that’s where Vikings originated. Some large brands such as SKF and IKEA might be recognised, but as I was told on a previous field trip to China, there are quite a number of Chinese who see Volvo Cars as Chinese originated. All too often, not just for those in China, but elsewhere too, Sweden has been confused with Switzerland.

For the Swedes on the other hand, China had been a long familiar concept. Early on, the country of China had become associated with various luxury items such as silk, tea and porcelain. Items that were not possible at the time to either cultivate or produce in Europe whether for natural climatic reasons or for the lack of know-how.

Swedish poet Evert Taube (1890 to 1976) composed songs about Shi Huangdi and the Great Wall of China. Sweden could be described as being quite enamoured with China from very early on.

[SLIDE 9]

The 18th century could be marked as Sweden’s golden age of trade with China. For the first time, Chinese exports could reach Europe by sea and the establishment of the Swedish East India Company by Colin Campbell and Nicholas Sahlgren meant that Chinese goods could reach new markets.

It was also during this period that Sweden went through the era of Enlightenment and Rococo became fashionable as a style of art, music and architecture. To the Europeans, China had a great history and it was written that China had a very sensible ruling policy, the epitome of true enlightenment.

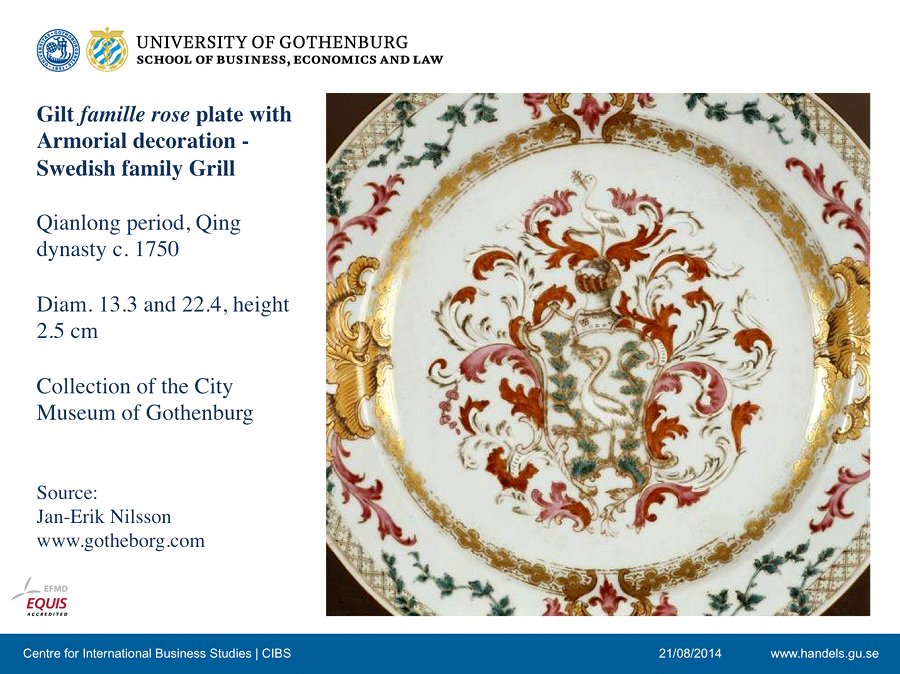

[SLIDE 10]

Europe’s appetite for luxury was also growing at the time, and while it was the upper echelons of society that could afford oriental flair, there as a growing middle class of affluence who wanted to mark their social status by increasing consumption of Chinese import goods.

Here is an example of what was imported from China at the time of 1750s, Amorial porcelain. This is one ordered for the Grill Family in Sweden, with the Crane as the symbol of the family’s Coat of Arms. This was part of the chinoiserie that blossomed in Sweden and Europe. Chinoiserie is a Sino-European mix of taste of the influence of Chinese products and arts that the European artists imitated.

So Sweden and China traded in not just material goods but fringing the goods were also exchanges in knowledge, in cultural transfers.

[SLIDE 11]

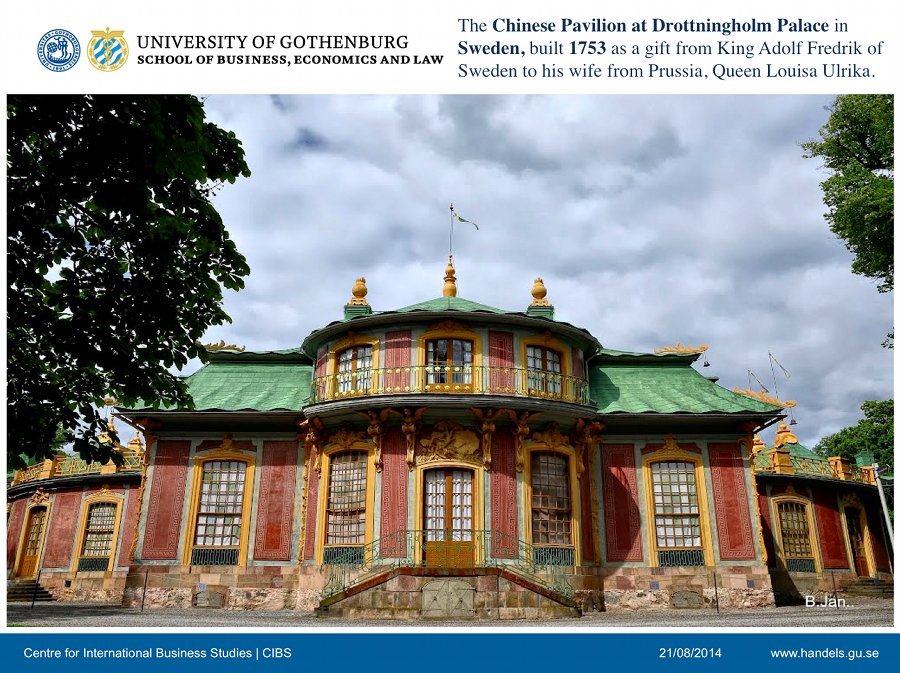

As a still standing example of how ideas and knowledge flowed from China to Sweden during the 1700s, not just goods, is the Chinese Pavilion or Kina Slott, built in 1753 as a gift of King Adolf Fredrik to his Prussian born wife, Queen Louisa Ulrika.

It was the Queen who had taken a strong interest in chinoiserie, and it was the supercargo to the Swedish East India Company, William Chambers who was given the task of decorating the interior Red and Yellow rooms of this castle. Each item was imported from China and the construction technique, was also Chinese. The King had made sure that his Cadet Corps were taught how to drill in the Chinese manner when building the pavilion.

[SLIDE 12]

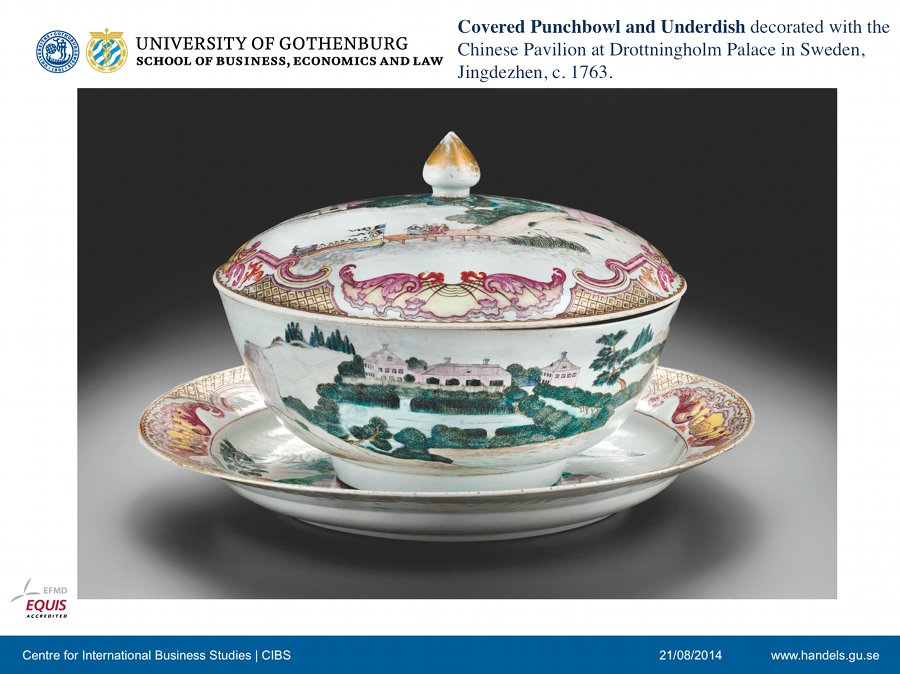

And here you see from the Peabody Essex Museum collection of Chinese export ceramics, the Swedish Chinese Pavilion on a covered punch bowl and underdish, decorated with the theme. This was made around ca. 1763.

The scenes depicted on this bowl, cover, and underdish appear to represent a fairly precise moment in the history of the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm. The original pavilion, built by King Adolf Fredrik (1710-1771) as a temporary folly for the birthday of Queen Louisa Ulrika (1720-1782) and presented to her on July 24, 1753, was a fantasy re-creation of the Cathay she so loved. Additional supporting buildings were then constructed: the king’s pavilion (seen at the right of the Chinese Pavilion) was completed in 1757, and the Confidence (at the left), where meals were taken, which was begun in 1758 but not completed until about 1763. Only four covered punchbowls with underdishes decorated with Swedish scenes are known; two others are known with Danish scenes.

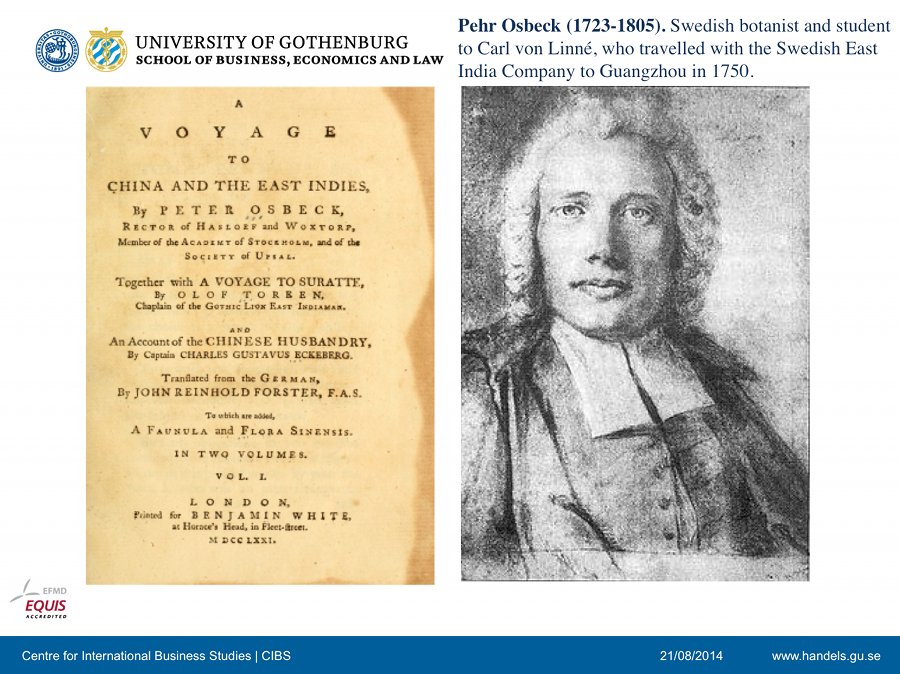

So you can see how Sweden and China had contact at different levels of society, including academia because one of the ship’s captains, Carl Gustav Ekeberg (1716-84) was member of the Academy of Sciences. And prominent Swedes such as Pehr Osbeck

[SLIDE 13]

who was a botanist and student to Carl von Linné, who had been to China during the 1700s, wrote about their voyages, often with a very positive outlook.

They wrote about how the streets of Guangzhou were very clean and how the Chinese parents were parenting their children in a good manner. There were some cultural and social shocks, where due to the weather in China, it was described that the everyday workwear of the Chinese were very thin, as if wearing underwear as outerwear and how certain Chinese languages like the Cantonese could sound very jarring to the Swedish ears. It was described that listening to two Chinese talk was like witnessing a full blown tavern brawl heard several streets away, except it wasn’t one. They were just talking.

But things change and world history moved on.

After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars (1789-1799), Rococo was replaced by Classicism and Romanticism. It was a turbulent era in Europe in general and there were strong convictions about things should be and tolerance towards all things foreign, succumbed. With the founding thoughts in the tendency to classify and evaluate people according to race, region and skin colour, the west began to view China’s Qing dynasty as ‘barbaric’ and ‘uncivilized’.

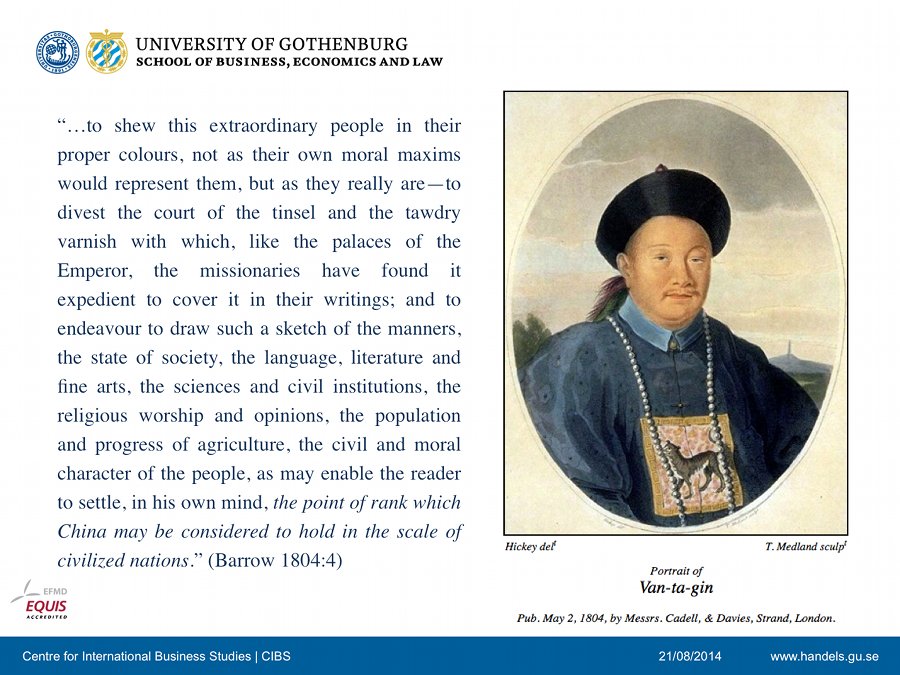

[SLIDE 14] (Barrow’s book)

This period is what could be marked as Europe’s turning inwards and onto a more ‘international society’ perspective, where the philosophies of Enlightenment scholars and their unqualified admiration for China were replaced by a more negative view of the country. And it was at this point too that throughout the west, there was a general growing dislike for all things Oriental and Chinese.

A noted book at the time was published in 1804 by British statesman and geographer, John Barrow with the purpose to:

“…to shew this extraordinary people in their proper colours, not as their own moral maxims would represent them, but as they really are—to divest the court of the tinsel and the tawdry varnish with which, like the palaces of the Emperor, the missionaries have found it expedient to cover it in their writings; and to endeavour to draw such a sketch of the manners, the state of society, the language, literature and fine arts, the sciences and civil institutions, the religious worship and opinions, the population and progress of agriculture, the civil and moral character of the people, as may enable the reader to settle, in his own mind, the point of rank which China may be considered to hold in the scale of civilized nations.” (Barrow 1804:4)

But not everyone shared this perspective. Sweden did not share this perspective.

And this is one of the defining points of Sweden’s friendly relations with China in the past, that Swedish authors and scholars continued to write positively about China and its culture, including August Strindberg (1849-1912) and Finnish Swede, Alexis Kuylenstierna (1862-1947), who wrote that China was as free as any western country and the Chinese citizens could travel throughout the country without papers and obligation to report to any authority.

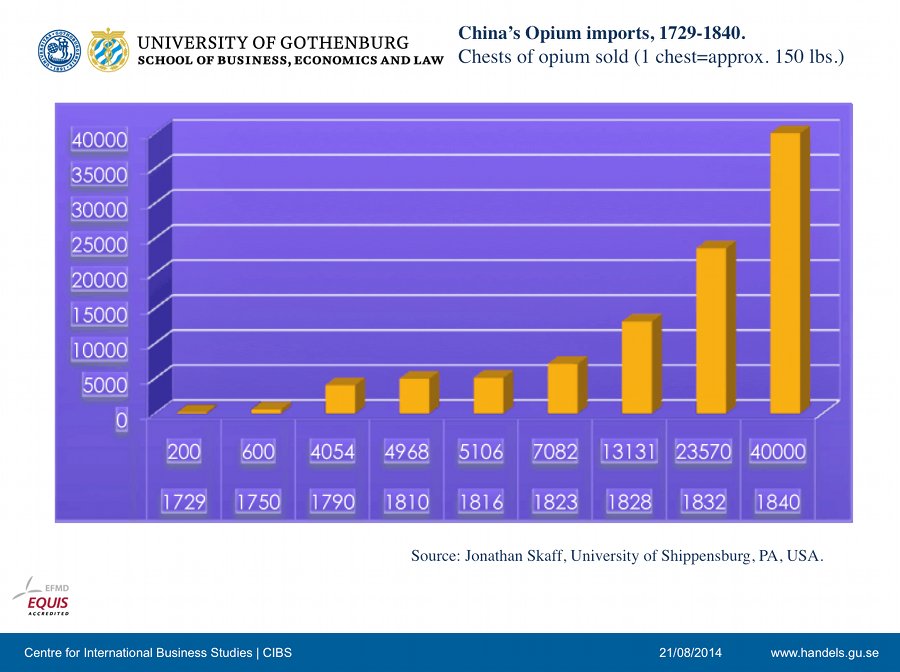

In the century of 1729 to 1829, and it was also during the Emperor Daoguang’s reign and at the time of John Barrow’s book publication that China saw its import of opium rise at an exponential rate.

[SLIDE 15] (opium import by no. of chests)

Due to a combination of factors, whether it was a drought that caused a poor harvest, together with the fact that opium was addictive that led to an increasingly ailing and drug dependent population, In 1839, Governor Lin Zexu enforced what might be known as the history’s biggest drug seizure that led to the armed conflict erupting between Great Britain and China, that is today known as the Opium War.

This ended with a military defeat of the Qing Dynasty who was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, the first of several other unequal treaties, and they were forced to yield Hong Kong to the British in compensation for the opium destroyed. Five trading ports were opened for trading that included the expanding city of Shanghai and the trade monopoly of the Canton System ended.

In retrospect, the west would have needed to have reacted more sharply on British dealings with China. Even the more positive and neutral Sweden seemed to have failed on this account. But it was also during this time that the first treaty between Norway, Sweden and China were signed by businessman and diplomat Carl Fredrik Liljewalch (1769-1870). And he too was in no way negative to China, turning against those who wrote about China as a tyranny with severe penalties and talked about misunderstandings and exaggerations. The tolerant nature of the Chinese was emphasized.

The main point in Sweden’s official stance towards China during the Opium War, that made it different from other western powers was that it had no plans to divide China into “spheres of interest” or “extorted leases”.

The government of Sweden did not believe in colonization.

[SLIDE 16]

And as an example of how much it didn’t believe in it, Sweden sold its last colony, St. Barthélémy in the Caribbean islands, in 1878.

[SLIDE 17]

But it still look some years before all treaties could be revised to the benefit of China. In 1908 the treaty between Sweden and China was made so that the Chinese were given the same rights in Sweden, as the Swedes in China.

This concession was mostly symbolic, but it paved the way for the powers of the future.

To summarise the ideas shared in this presentation:

There is something to learn from the friendly and peaceful relations of these two countries that go back centuries. The two countries have somehow managed to find a balance in operating between in ‘international society’ and a ‘global society’. That you do not need to conquer the Other in order to benefit yourself.

From Sweden and China, it was the mutual recognition of fair trade from both sides. Their relations illustrated a recognition that the globe had many value systems

[SLIDE 18]

under one larger value system.

[SLIDE 19]

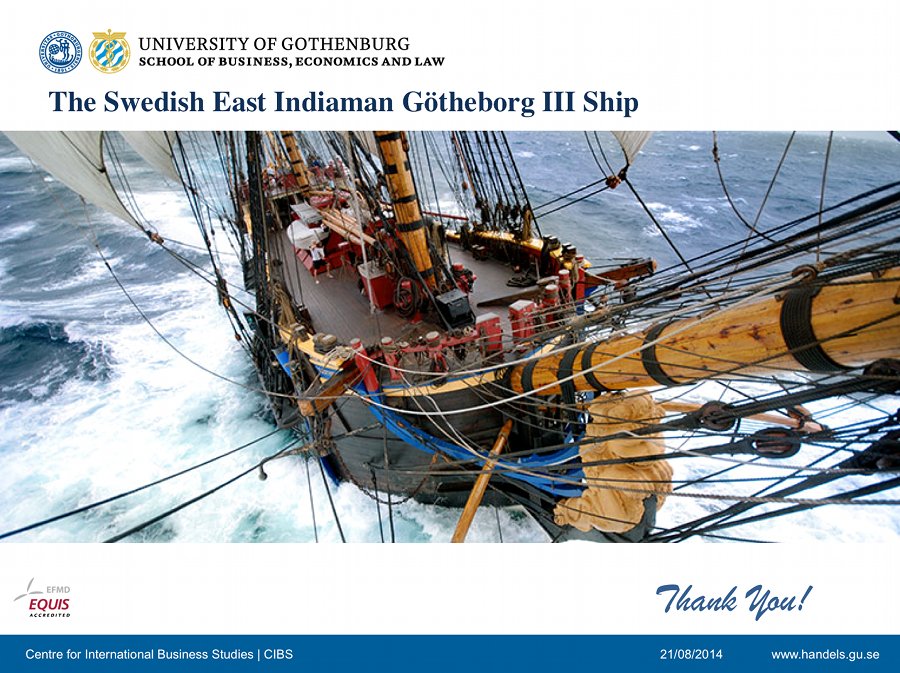

Today, the Gotheborg III Ship continues to sail in recognition and honour of this traditional knowledge.

[SLIDE 20]

A traditional knowledge that is shared by both Sweden and China, where hopefully lessons learnt in history, can help pave the way for future relations, and set an example for other countries to follow, of peaceful trade, of continued exchange of knowledge towards a global society.

Thank you for your time, and thank you for listening.