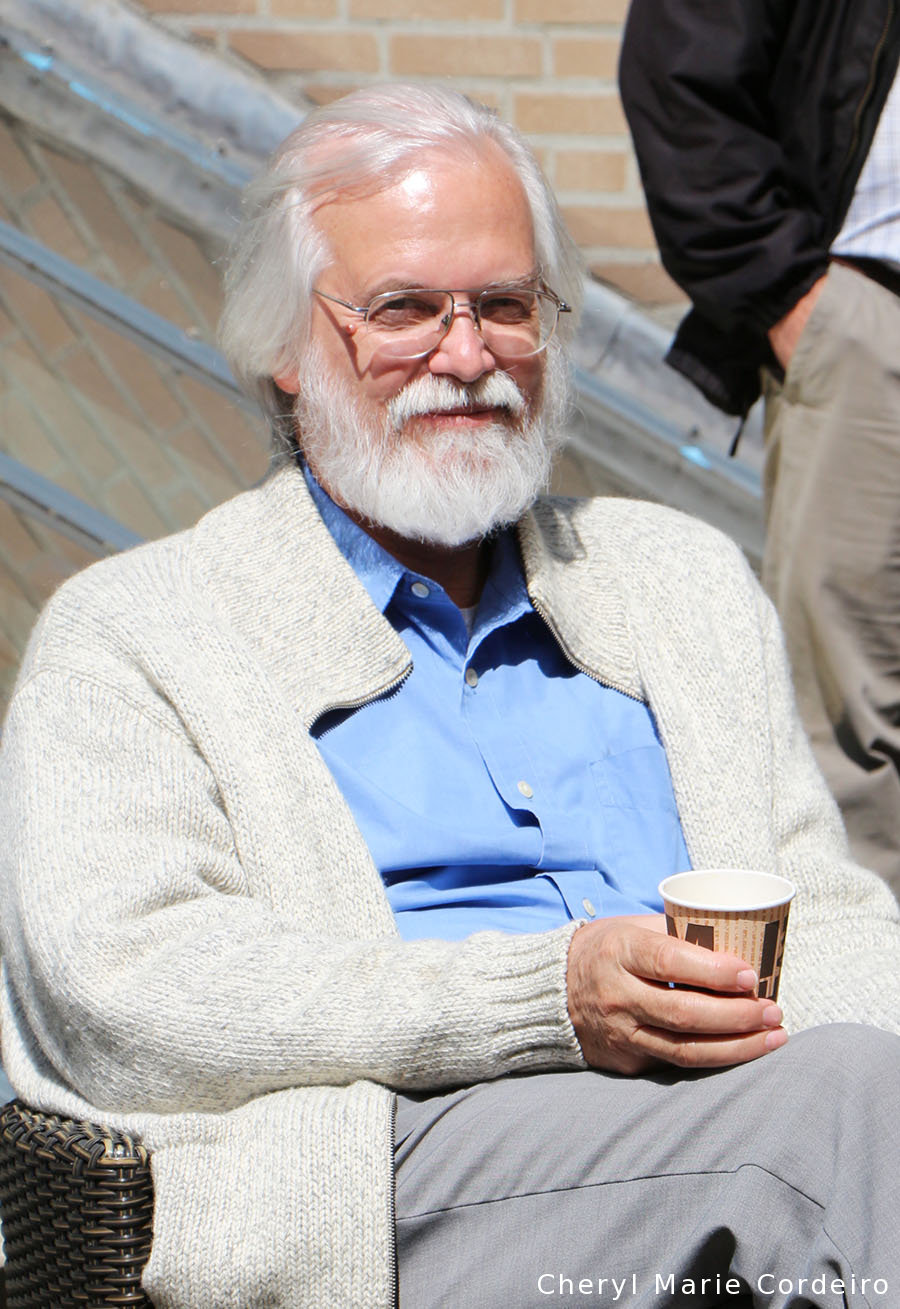

Dr. Cheryl Marie Cordeiro with Emeritus Professor Geert Hofstede, showing his University of Gothenburg ring where he has been conferred the title of Doctor Honoris Causa. He has eight honorary doctorates, that include those at Nyenrode, Sofia, Athens, Pécs, Liège and Vilnius.

Text & Photo © CM Cordeiro, Sweden 2015

The 10th Global and Cross Cultural Organizational Research Ph.D. Workshop and Conference was hosted by the Hofstede Chair, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASoS) at Maastricht University, Netherlands from 14 to 19 June 2015.

The week-long programme that was held in seminar format, provided a platform for doctoral and post-doctoral students interested in organizational culture studies research to meet with some prominent and influential scholars of the field. The noted guest lecturers to the programme included distinguished scholar Geert Hofstede, Professor Emeritus of Organizational Anthropology and International Management at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, and Mikael Minkov, Professor of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Organizational Behavior at International University College, Bulgaria. Minkov has co-authored several publications with Hofstede, and is known for his quantitative cross-cultural analysis across modern nations that led to a development and update of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory and model.

In a reversal of knowledge sharing and learning techniques, where instead of questioning the participants on the extent they have understood the course literature provided in advance to the start of the programme, programme coordinators Mark F. Peterson, holder of the Hofstede Chair in Cultural Diversity at Maastricht University and Professor of International Management at Florida Atlantic University, and Mikael Søndergaard, Professor of International Management at Aarhus University, Denmark, gave a perfect overview of the field of cross cultural organizational research. The topics covered fundamental assumptions in cross cultural research, its origins from anthropology to psychology, early and current works, methodology and future avenues of research in the field. Participants were most of all encouraged to ask questions on concepts and methods not understood, and to comment on personal insights gained during the programme.

The programme allowed room for flexibility in inquiry on the part of the participant, so that any related topic of interest not covered in the formal programme could also be elaborated upon and facilitated for discussion by request of the participant. This strategy, coupled with the open discussion format of the seminar, provided good grounds for networking between all scholars present.

Different from previous gatherings, it was shared that the 2015 cohort were by far the most mature group of participants the programme has seen in a decade. With four post-doctoral participants, this was the highest number of post-docs thus far to be enrolled in the programme. The national diversity was also high with about fifteen participants representing ten nations, excluding the fact that many of the participants themselves had mixed cultural heritage, making them effectively bi-cultural and bi-lingual individuals.

A personal takeaway from the programme is the insight that the study of organisational culture itself comprises an eclectic mix of theories and methods, with its findings depending upon the perspective from which the inquiry is launched. The various contributing knowledge paradigms makes the field diverse and one of rich interest precisely because one inherently studies what it is to be human when studying culture:

“The facts of human biology are, of necessity, facts of human culture in three ways. First, our evolutionary lineage has been coevolving with technology for millions of years, and consequently the environment into which our own species evolved and adapted was necessarily a cultural one; culture is an ultimate evolutionary cause of human biological facts. Second, as individuals we develop within environments that are profoundly cultural, ranging from uterine conditions to postnatal nutrition, exercise, social stimulation, child-rearing practices, and personal experiences; culture is a proximate physiological cause of human biological facts. And third, these facts have always been produced in a context of conflicting interests of patronage, political ideologies of diverse kinds, professional aspirations, and cultural expectations, and they still are” [1]

The above observation by Jasanoff in 2004 makes explicit that culture can be studied as both phenomenon and/or process, the former of which is inherently multifaceted in nature, to which multi-levelled analyses can be applied depending on choice of perspective.

The differences in ontological and epistemological paradigms in the study of culture is also taken up in discussion by Lee, Kim and Park [2] in their study on culture clashes in cross-border mergers and acquisitions, using Sweden’s Volvo and South Korea’s Samsung as case study:

“Apparently, the classic and the social constructivist concepts of culture are essentially incommensurable as they are deeply rooted in fundamentally different ontological and epistemological paradigms. While the former sees culture as an objective reality that ‘‘exists’’ out there and thus can be studied as if it is a bit of the physical world, the latter sees it merely as a social construction of reality [3]. Therefore, one may argue that they must be developed and applied separately in different scientific disciplines.”

Viewed in this light, what Hofstede had done with his cultural dimensions (CD) construct was to provide the field of culture studies from an organizational perspective, a toolbox that allows for the operationalizing of the concept of culture. The CD theory and framework, while necessarily takes only national averages which subsequently means that no one individual within any national border can accurately be accounted for, can nonetheless be used to systematically measure, compare and predict consequences for certain contexts of the meetings of different peoples.

It is however not solely in academic publications that point-of-view is addressed. In one of my favourite reads entitled, I Married a Barbarian [4], co-authors Bloodworth and Liang, who are husband and wife of different cultural backgrounds, she being Chinese and he being British, sharing no common language to begin with in their relationship, noted that:

”People must always see each other through their own blinker-visioned eyes – who else’s? – and in consequence get a distorted picture. An American’s subjective image of the Chinese and a Chinese’s subjective image of the Americans might well leave them both wondering who the hell the other was talking about.” (by Bloodworth:168)

”’Even dragons have nine kinds, but all dragons.'” (by Liang:9)

The last day of the programme was spent much in contemplation that with all that has been done in the field of the study of organizational culture, what then for the future?

I think the answer might well be on its way in the manner proven in the history of academic studies, that discoveries in natural sciences have often influenced and impacted theories and perspectives in social sciences:

”The sixties are underway, we’re going to the moon in a big way. Everybody knows it. We are innovative culture. You know it’s an innovative culture because every week, every month, a new advance in space garners the headlines because a space frontier is being breached. A space frontier. When you breach a space frontier there’s something new to talk about in that day’s paper. Something new to talk about.” [13:20ff]

”Our presence in space is not only affecting the engineers, the mathematicians and the scientists. It’s affecting the creative dimension of that which we call culture. We are living it, at every turn.” [17:02ff] – Neil deGrasse Tyson, 2012. Keynote speech on Space as Culture, at the 28th National Space Symposium, held April 16-19 at The Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs [5].

Studies in fields of science such as cosmology, astrophysics, quantum physics, as well as in the field of biology, the Human Genome Diversity Project [6], studies on epigenetics, the inheriting of memory and the Lamarckian brain [7], and exploring interactions between biological evolution and cultural change [8] might all be interesting influences on how organizational studies might view culture in the near future.

Culture, even if studied as an object / phenomenon, is a living, evolving entity. Any study that does not focus on culture as reflecting a longitudinal process of socio-political change will necessarily provide instantaneous findings. As such possible interest in future avenues of research in the field could be to study the evolutionary changes in culture.

Mark F. Peterson, holder of the Hofstede Chair in Cultural Diversity at Maastricht University and Professor of International Management at Florida Atlantic University.

Front row, (left) Mikael Søndergaard, Professor of International Management at Aarhus University, Denmark, (right) Geert Hofstede, Professor Emeritus of Organizational Anthropology and International Management at Maastricht University in the Netherlands.

Front row (L-R): Mikael Minkov, Professor of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Organizational Behavior at International University College, Bulgaria, Professor Mikael Søndergaard, Emeritus Professor Geert Hofstede, Professor Mark F. Peterson.

References

[1] Jasanoff S. 2004. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. New York: Routledge.

[2] Lee, S., Kim, J., & Park, B. I. 2015. Culture clashes in cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A case study of Sweden’s Volvo and South Korea’s Samsung. International Business Review, 24(4), 580-593. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.10.016

[3] Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. 1979. Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. London: Heinemann.

[4] Bloodworth, D. & Liang, C.P. 2000. I Married a Barbarian. Times Books International.

[5] Tyson, N. deGrasse 2012.Keynote speech on public and government re-engagement with space, and space as culture, 28th National Space Symposium and its companion Cyber 1.2, April 16-19, The Broadmoor Hotel, Colorado Springs. Internet video resource at http://bit.ly/1JBTe9M. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

[6] Barker, J. 2004. The human genome diversity project: ’peoples’, ’populations’ and the cultural politics of identification. Cultural Studies, 18(4), 571-606. doi:10.1080/0950238042000232244

[7] Fischer, A. 2014. Epigenetic memory: The lamarckian brain. The EMBO Journal, 33(9), 945-967. doi:10.1002/embj.201387637

[8] Laland, K. N., Odling-Smee, J., & Feldman, M. W. 2000. Niche construction, biological evolution, and cultural change. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(1), 131-146. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00002417