Wilted, at Zhouzhuang water village, Jiangsu, China.

Text & Photo © JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro 2014

As if apologetic that all I’ve experienced this time in Shanghai in terms of weather was rain and grey skies, the weather took a turn for the chirpier on the day I was to visit Zhouzhuang, deciding to turn on sunshine at full blast. This was not so much seen as already felt in the early hours after sunrise. Standing under the concrete shelters of the hotel, I had already begun to swelter.

In the taxi queue where I was instructed to wait for the tour bus by the concierge, stood my colleague waiting for his taxi to arrive, on his way to a meeting. He peered at the ticket I held in hand, ”You’re going to Zhouzhuang in a private car? That’s fancy!”

I checked the ticket in hand and was certain that the concierge had indicated a tour bus, ”Actually not. I’m expecting a tour bus of some sort, if not a mini-tour van, something like that, but it’s late.”

”Oh really? Which company’s taking you there? Maybe it’ll be easier if you could spot the bus with the logo all over it.”

I located the company logo on the ticket which said, ”Vacation China” and smiled. Right, that would be it.

After another fifteen minutes, a check with the concierge indicated that the tour bus was on the way, but due to the heavy morning traffic in Shanghai, it was delayed. From where I stood, I could see the morning traffic outside of the floor to ceiling glass doors of the hotel, the roads looked uncluttered as a cloister after morning mass. I nodded and agreed that the traffic was heavy and yes, the bus would arrive sooner or later.

After about an hour’s wait, the concierge came with the news that it seemed that the tour bus did forget to pick me up along the way, and déjàvu, a private car was now here with two individuals, a driver and an English speaking tour guide:

”Sorry ah Miss, but the tour bus driver, he forgot you. And then the agency called both of us.” Pointing to the driver, the tour guide continued, ”He was sleeping, and I was drinking my morning coffee at home when the agency called us to come pick you up. So we both rushed here to now bring you to Zhouzhuang. It takes one hour fifteen minutes from here, okay? Do you want water?”

Actually, I didn’t need another bottle of water, in fact I had so far tried (and failed) to return two unopened bottles of water to the concierge, who had insisted on giving me bottles of water to pacify and in apology of a no show of tour bus. ”No, it’s okay, I’ve got my own.” I smiled.

Braised pork shanks. From halfway to Zhouzhuang to into the water village itself, there were more than twenty food stalls and outlets selling exactly this – braised pork shanks – in close range of each other that got me wondering just how many pork shanks were eaten on a daily basis? And of all possible visitors from different countries, which country liked them best? And could the answers be explained via culinary proximity theory (assuming there was a culinary proximity theory in the first place)?

As we began our drive out of the city of Shanghai, encountering the farmlands of Jiangsu province, the tour guide turned to me and said, ”Here you will notice that the lands are very very flat. In fact, there are no mountains to see here in this part of China, which is why they can grow things.” He then directed my attention out the window of the car, ”You see, no mountains at all. And only a lot of land, all land, no waterways also.”

With that, having not quite adjusted to the time in Shanghai from Gothenburg, and having had little or no sleep the past few nights, I pushed my weight back into the seat of the car, closed my eyes, and promptly fell asleep.

I awoke when the car pulled up to the tourist ticketing office and the tour guide, on his way out of the car, instructed me to, ”Please stay here and don’t go away. And if you do go away, please come back to the car, okay?”

Okay.

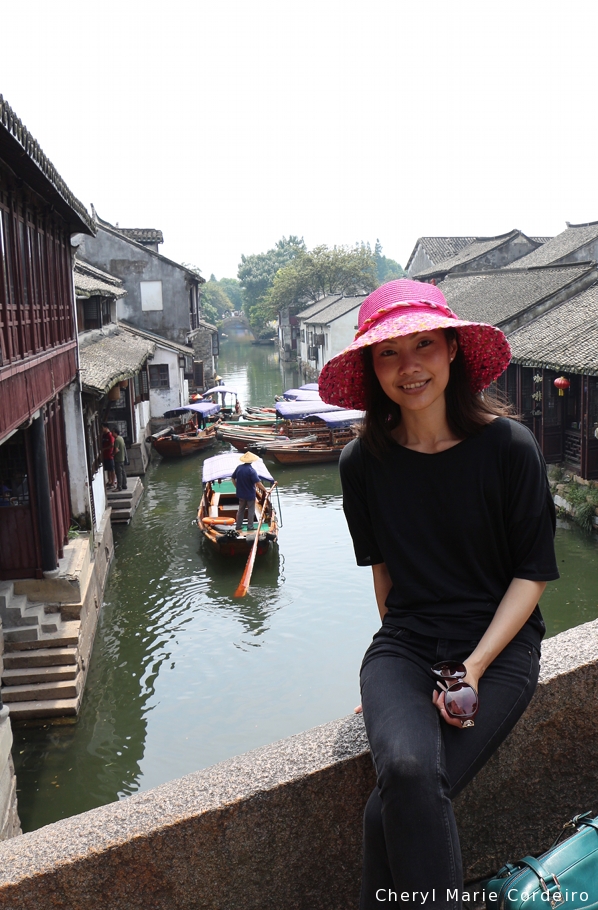

A bridge. One of many at Zhouzhuang.

Upon entering the water village that by now, I’ve come to hear over and over, ”It’s the Venice of the East!” in variations of excited tones, I was actually struck by how very similar it was to Venice in terms of the sheer number of visitors – by the bus loads – that were ploughing through the cobbled streets and onto the tiny ancient bridges that threatened to collapse under the weight of the visitors standing on top (mine included). It was near impossible to see to the end of any street at any one time, and you might need to intentionally knock someone over the bridge in order to find yourself a good photo spot.

”This town, is very old. You see the buildings?” the tour guide pointed to one that was particularly in need of roof repair, ”All were built hundreds of years ago.”

I nodded, following his quick steps and side dodges through other moving bodies in the crowd and figured, he might do very well navigating the MRT underground of populous Singapore at peak hour, ”So how did this village become a tourist attraction? What’s its story?” I asked.

”Well, actually it was only a small ancient village. Then one day, some tourists began to notice it. And then, more and more. And the locals, they decided that if the tourists are interested, it was better if they turned their houses into business. So now you see, all business is at the bottom floor, only the second floor, some people living there. Otherwise, it’s all business. You can buy a lot of things here, you can also eat here. But today, we are only on a half day tour, so lunch not included.”

”It’s okay, I don’t do lunch.” I laughed slightly, both at the chafe in his tone of voice of the place and of the downright pragmatic approach to life in general that created the Chinese model of endurance, ”You seem to know this place very well. You’ve been here a lot?” I asked.

”Very many times. Thousands and thousands of times!” said the tour guide. Clearly the romance of Zhouzhuang had long washed from his eyes, the old stones are old stones and the boat ride is a boat ride. And as point to prove, he was at that moment approached by another visitor, a woman with children in tow who asked directions to a certain point of interest in the water village, ”Yes, this place, ” he said. ”You walk right down here, straight, till you see the building with a tea house. Turn left and continue walking straight, you get there. Make sure you see the tea house first, or else you’ll make a wrong turn.” As soon as the visitor was on her way with children, so was the tour guide. I trotted behind him.

Surveillance. For when one ancient stone comes undone in its place.

The boat ride.

It soon came that the tour guide brought me to where the bumboats were, for a boat ride. ”This boat takes six persons. With you in it, there will be already six persons. So I will not join you in this boat ride. I cannot help you take pictures. If you want pictures, ask that man there who is also on the same boat. I will wait for you at the other side, okay?” Okay. I thought it super efficient that everything was arranged, in double speed.

From the bustle of the streets to the dodging of crowds, life for fifteen minutes or so on the boat took on a different time altogether. The pace slowed, and the man who steered and rowed the boat, began to sing us songs of peace, harmony in life and one of wishing us travelers, a safe journey home. At this moment in time, I thought – this, was Zhouzhuang – this was what I came to feel, to see. Though the experience of going through the water ways could well echo Venice, the vibes that came through the well worn walls of the houses, the waters from below and of the tones of voice of the people who lived there, were far from anything like Venice at all. It’s a different world, anchored in a different kind of traditional knowledge.

The boat ride offered insight from the perspective of one being in the middle of local life (the waterways) yet still looking from outside in from the canals as non-locals. As the bumboats passed through, you could see that the people were living now as they always had from generations ago, before the visitors had arrived. Newly washed cotton were hung out to dry under the sun on strings or bamboo poles. Utensils were washed in the waters, and children played on bamboo structures hovering above the waters. Still other scenarios, people gardened and tended to their ripening gourds that hung heavily on supporting bamboo structures in vines, also close to the water’s edge.

The place, with its people and its living untouched, is strikingly beautiful.

Tea house. Tea.

Pointing to some pasted news clippings on one wall of the tea house, the tour guide turned to me and said, ”And here, you see here, it’s a very famous actress. She committed suicide. She used to come here, that’s why her photo is here on the wall.” I nodded in acknowledgement and took a closer look at the wall. Yes indeed, I could see how she appreciated the tea and wondered if by now, any import of ideas from the west north, would have them serving some tea infused with blueberry?

But all too soon, the boat ride ended and I found myself back on land, once again navigating the street crowd.

Passing by a temple, I asked the tour guide if I could go in for a look.

”This temple, not very old.” he said, shaking his head. ”It’s a Taoist Temple. Not very old at all.”

We went in, anyway, where he waited just two steps in of the temple’s main entrance.

After about fifteen minutes of no show on my side, the tour guide came searching for me and was surprised to have found me sitting seiza beside the main altar, in contemplation. Looking curious for the first time since stepping into Zhouzhuang himself, the tour guide reiterated, ”This is a Taoist Temple.”

”Yes, it is.” I replied.

Chengxu Taoist Temple.

Bamboo crafts.

From cotton weavers and wood carvers to calligraphers, Zhouzhuang is filled with craftsman who today cater for the tourist industry.

Outside the Strange Loft.

”You want to go in?” the tour guide asked.

I am as always, curious, ”What’s in it?”

”Inside, have ghosts.”

”You mean man-made or real ghosts?”

”It’s real, it’s real. I don’t think you want to go in.”

And there I thought, ”Hmm…”

But more than the presence of said ghosts in the house was the tour guide’s face coming to being ashen with hunger that kept me from going into the Strange Loft. ”What time is it? You must be hungry by now?” I asked.

A local favourite – or in the least, the tour guide’s favourite – pork chop in noodles.

Towards the end of our walk around the water village, it was not I who needed lunch, but he, the tour guide. And in that light, I was led to a tributary lane of Zhouzhuang, to a restaurant owned by a friend of his, who then brought out two bowls of noodles at almost no cost.

Considering the start to his working day of an interrupted morning coffee, I thought this was a pleasant winding up of the afternoon where I got to eat at a non-tourist designated eatery and was actually introduced to one of the tour guide’s favourite noodle places in Suzhou, where he lived with his family.

It was in a paper entitled Innovation in emerging markets – the case of China by George Yip and Bruce McKern (2014:4) that the authors wrote of China’s enablers of innovation in its post 1978 reform years, citing ”the famed entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese business people, well demonstrated for many decades outside mainland China.” I thought it surreal that one need not in particular travel outside of the country to witness the evolution of business landscapes in China. Pre- or post reform years, the spirit of entrepreneurship runs through much of the fabric of the Chinese society.

I think I could spend much more time at Zhouzhuang at a less hurried pace, wandering the back lanes of back lanes. Depending on what is yet to come in terms of catering for tourists, what can be hoped is that the people here find a balanced integration of lifestyle that incorporates visitors and their own local living / heritage. And that the numerous romantic bridges will continue to stand, for many more years to come.

Reference

Yip, George / McKern, Bruce 2014. Innovation in emerging markets – the case of China, International Journal of Emerging Markets, 9(1):2-10.