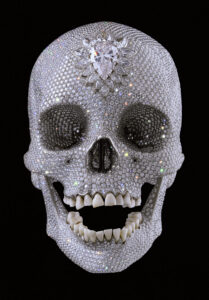

British artist Damien Hirst revealed his latest work of art at the White Cube Gallery in London, June 1, 2007. ”For the Love of God” is a life-size cast of a human skull in platinum and covered by 8,601 pave-set diamonds weighing 1,106.18 carats. The single large diamond in the middle of the forehead is a 52.4 carat internally flawless, light, fancy pink, brilliant-cut diamond reportedly worth $4.2 million alone. Hirst financed the project himself, and estimates it cost between 10 and 15 million. The price tag was $99 million. The platinum plates were hand-lasered with thousands of holes and the diamonds, which have a total weight of 1,106.18 carats, were individually set.

When I first saw this skull I went through a myriad of reactions that went something like:

WOW! What a fantastic thing!

Oooh! How HORRID!

buuuuut…Interesting.

COOOOOL!

Well, my thoughts needed to do a really long walking to come to that fourth observation of it being cool. The obvious in-your-face impression of this piece of art, is of course that the skull as an age old Vanitas symbol that Nothing is Forever, combined with the De Beer diamond slogan that Diamonds, are Forever, Hirst manages to add some kind of cynical humour to the combination ”Death, is Forever, too”.

How cool is that.

Then I started to wonder, is that observation really worth £50 million?

My mind started to ponder a much wider circle. Looking some into this I found that the original ”perfectly shaped skull” had been sourced from a taxidermy shop, with an analysis suggesting that it had probably belonged to a European man who died in his mid-thirties in the 18th or early 19th century.

But don’t those teeth awfully “fresh” to be from an 18th century skull?

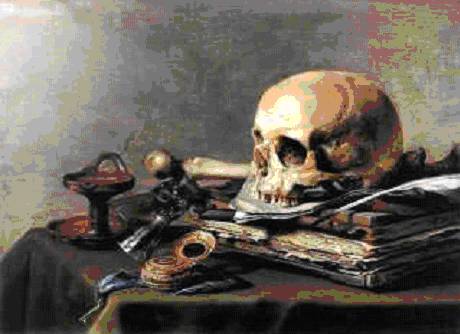

A really old skull. The painting ”Vanitas” by, Pieter Claesz (1597-1661).

It suddenly dawned on me that I had seen such a ”fresh” looking skull once before, at the desk of an engineer who designed dental equipment. “Is this plastic?”, I asked. “No, it’s the real thing” he answered and explained that it actually came from the first World War battle fields in the Flanders. They were popular with dental clinics because the soldiers had been so young and healthy when they died, that their teeth were perfect, ”Look Ma, no cavities!”.

Of course this was just my mind wandering, but then again I had just been forced – due to a lack of alternatives – to read an article about a specifically bloody battle in an obscure village in Belgium, called Passchendaele. It lasted some 100 days in the autumn of 1917. And when it ended, a total of 325,000 Allied and 260,000 German young men had died, achieving nothing.

Of course it was a long time ago, but haven’t we all wondered how come it was so necessary to grind down so many young soldiers at the ”Western front” during the First World War? Millions and millions of young men were sent there to die at a front that just did not budge.

Australian gunners on a duckboard track in Château Wood near Passchendaele, 29 October 1917. Photo by Frank Hurley.

In that article that I read, they explained that the whole point with this battle of Passchendaele was to try to ”put a stop to the German submarine base at the Belgian coast, from the land side. The thing was that the German submarines had become a serious pain in the butt for the British merchant navy, at the time. Expressed in cold numbers, the 5 to 10 ships that were lost every day was not only lives lost, it was also money. And one fifth of that was picked up by the private underwrites of I would assume, Lloyd’s in London. You might all know Lloyd’s as the insurance company where Jennifer Lopez reputedly insured her most important asset – her bottom (not true) and Heidi Klum insured her legs (true).

So standing at Old Bond Street in London and looking at a picture of this skull in a shop window, I couldn’t help feeling a certain discomfort of mysteries unfolding, creeping over me. There are just so many myths and legends connected to London, you sense, as it were, the shadow of Jack the Ripper around any corner you pass.

Another one of those snippets of facts I remembered was that the Lloyd’s underwriters – you know those who pay up if something bad happens ”down to their last collar button” were by and large found among the British nobility. In an old Time magazine I once read it explained that these underwriters at the time of writing (Aug 16, 1963) embraced 5,316 British moneyed members amongst which four were Cabinet ministers, 52 Ministers of Parliament, five Dukes, eight Marquises, 39 Earls, 90 Knights and 113 Baronets. As a payoff they averaged a cool 8% return on the money they risked. Easy money, if nothing bad happens.

But ”something bad” did happen, with the outbreak of the WWI. A very small number of German submarines, numbering around ten, started to sink British ships. The losses were mounting. So with each and every gray hull tumbling down into the abyss, a mountain of financial loss grew. This loss dug directly into the pockets of the Lloyd’s underwriters, still raw from the 5$ million loss incurred by the loss of the Titanic in 1912.

It is certainly too broad a sweep of me to theorize that the possible loss of money on the part of the British nobility could have had any importance whatsoever in the decision of something as serious as a war strategy that cost millions of mens lives. But my point is that these thoughts were the workings of the controversial, diamond encrusted skull of Hirst’s.

With regards to Hirst’s skull being one of the most expensive pieces of art thus sold, I rather felt it was a splendid example of what Marcel Duchamp meant with his Ready-mades, to show that anything displayed as a piece of art creates art by the interaction between the object and the viewer. Such as when an ordinary object – like a skull and diamonds – is put in a formal exhibition space.

Considering that even the year matches – 1917 – between the battle of Passchendaele and when Marcel Duchamp exhibited his most notorious Ready-made, the Fountain (a replica now in Tate Gallery in London), is it even possible to think that this is a coincidence?

Photo: Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

From the Tate Gallery:

”Fountain 1917, replica 1964

Porcelain

unconfirmed: 360 x 480 x 610 mm

sculpture

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1999

T07573

Fountain is the most famous of Duchamp’s so-called ready-made sculptures ordinary manufactured objects designated by the artist as works of art. It epitomises the assault on convention and accepted notions of art for which Duchamp became known. The original, which is now lost, consisted of a standard urinal, laid flat on its back and signed with a pseudonym, ’R. Mutt 1917’. This work is one of a small number of replicas which Duchamp authorised in 1964, based on a photograph of the original by Alfred Stieglitz. (From the display caption September 2004)”

With the interaction between viewer and object, object and history – suddenly this diamond studded skull made so much more sense to me. Its cynical grin stood out to me as a message from the trenches of Flanders, with a 57-carat internally flawless pink diamond looking hauntingly like the face of an iconic Lucifer on its forehead, because so cut is a pear shaped diamond that one can imagine a set of ”eyes” staring back at you, from most angles of the stone.

The subtle irony (intended or not) is so totally well worth its £50 million price, the surreal amount of money actually being a part of the artwork.

When next you are in London, don’t miss the Tate Gallery of Modern Art; that beside one of Duchamps Ready-mades serve a mean hot chocolate in the restaurant. Totally best, ever, hot chocolate!

Internet Bibliography

- ABC News

- artnewsblog.com

- bbc.co.uk

- Bloomberg

- Boing Boing.net

- Dagens Nyheter

- Dagens Nyheter, an write-up on Chinese art, where Hirst is mentioned.

- Daily Mail

- Guardian unlimited

- New York Times

- The Scotsman

- thisislondon.co.uk

- Reuters

- Whitecube