ArtScience Museum, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore.

Text & Photo © JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro 2014

Taxi drivers. They make some of the most understated ambassadors to a country, in particular, if that country is Singapore, if only because most taxi drivers are quite loquacious individuals who love spending time in transit to get to know their passengers.

Having not been back in Singapore for a couple of months, I had expected some kind of feedback when I landed in Singapore from Sweden, from family or friends about the climate, not just literally about the haze from Indonesian forest fires, but rather the political and cultural climate of the country. It seemed I had that opportunity however, on the incoming flight from Scandinavia on the airplane, sitting next to Ben, a 1980s born young man who had five years ago, married a woman from Malaysia. She was in fact, seated in an adjacent row with her sister. In the course of conversational exchange, Ben mentioned that he and his wife had no children as yet, “Even though we are five years married already.”

“Why not?” I enquired.

“No, we’re not thinking of having any children right now. We need to enjoy life and besides, we don’t see what children can bring for us these days.” I nodded in feedback and cast a brief glance to where his wife was seated with her sister.

“It’s expensive to have children” Ben continued, “And it’s very competitive! Everybody’s going to want to know what your child is up to, which school they go to, what grades they score, whether they train ballet or piano or something else. It’s too stressful. Before four years old, already got to know a lot of mathematics and several languages just to keep up!”

In the days to come, as I zipped around the country for various meetings of sorts, I began to hear narratives in similar tonal shades of complaints and grievances of life in the cosmopolitan city, shared by taxi drivers. The first narrative was shared by a brother to a renowned Singapore designer who had operation bases in Singapore and in Hong Kong, of their family run business. Lenny had described himself as the ‘black sheep’ of the family, except he rather used the word ‘tiger’, “Because every time I go to the family office, we sure disagree. So I’m very tiger, always create problems, questioning everything they do.” In the long winding crawl of peak hour expressway traffic, he was able to share with me, the family business story, it’s ups and downs in near chronological order since business began for them in the 1970s with their first outlet in C.K. Tang, “You know, when Orchard Road was not so developed yet? And C.K. Tang was one of the main department stores?” I nodded in response. ”Ah, we were first there you know.” he said proudly. Apart from family disagreements, Lenny generally felt that there was a lack of governmental support for the family business, “The government prefer foreign investments lah.” he concluded.

In the last leg of journey, when I was near my point of destination, I asked him to share what life was like at the time that C.K. Tang was one of Orchard Road’s major departmental establishments, “Life back then, was simple. Less stress. I prefer back then, not now. You know I lived through to see Singapore gain independence? I don’t think you were born then, but I was there. Now, my children, I don’t know what they are going to do in life. There is no job security even in the family business. Everything is money nowadays, and the business has shrunk a lot. There is no guarantee of income. The business environment nowadays also changes very fast. One day, there’s a factory in China, next day, the factory can be sold. You can’t trust people these days, especially those in China. It happened before. That’s why we pull out of China, we settle in Hong Kong instead. China, people think so easy to do business because we are Singapore.” He shook his head, ”China, very difficult to do business ah.” Our conversation ended on the note that Lenny did not like the foreign workers situation in Singapore, especially those who had recently settled in Singapore from mainland China, for whatever reason they might have. “Maybe it’s an experience thing, but I can also say, too many foreign workers. There is no consideration for Singaporeans on the government side, especially those who have been here for the country since the beginning.” He shook his head again.

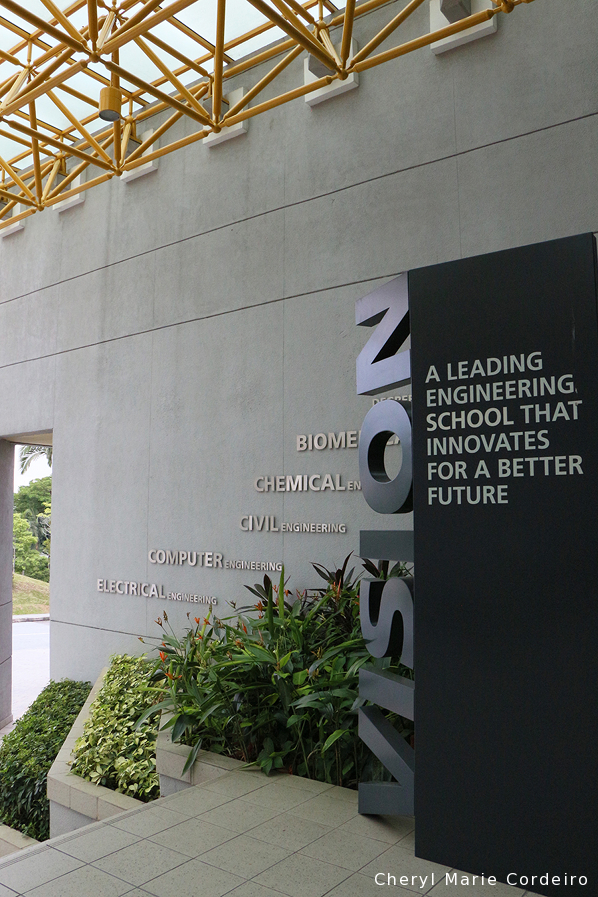

Cheryl Marie Cordeiro with Professor Bernard C.Y. Tan, Vice Provost (Undergraduate Education) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), at the 7th IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology (ICMIT2014). The conference was held at the NUS Engineering Faculty from 23 to 25 Sep 2014.

The next day, a tropical rainstorm was happily making its presence felt in the early hours of the morning when I needed to make my way towards the west end of Singapore. I found my way to the main road and decided to stand by the entrance of a petrol kiosk in hopes of flagging down a taxi. I noted with dismay that there were several individuals with umbrellas in hand, who had positioned themselves along the same stretch of road ahead of me facing the direction of oncoming traffic, also waiting for taxis. I registered that it could take a while before I got myself a taxi.

Conference river cruise.

Seeing that I might be late to the meeting, I made several attempts at dialling for a taxi in their phone booking reservation system. It took three tries to confirm that no taxis were available to be booked at the time. But in under five minutes of being declined any taxi bookings by phone, a taxi pulled into the petrol kiosk. Curiously, the taxi driver waved at me to wait for him. “Sorry ah” he said as he got out of the car, “but not everything is money. I need to go to the toilet! I’ll be back.” Smiling, I nodded, tucked away my wet umbrella, and patiently waited for him under the shade of the petrol kiosk – another white Mercedes-Benz taxi after yesterday’s pick-up – I noted. So my booking went through after all then?

To my surprise, the first words uttered by the taxi driver to me when he reappeared were, “Are you a Christian?” I looked at him, confused. “Well…” I hesitated, “You could say so. Why?” I asked.

“Do you pray a lot?” It sounded more of an implied accusation from him than a question. When I remained apprehensively silent, he continued, “You prayed for a taxi to come pick you up?”

“Actually, I made a phone call for a booking.” I remarked.

“No, no that’s not me. There were so many customers I passed up along the way, I needed the toilet and I know this petrol kiosk is the closest. So you are lucky, you were standing here. Raining some more!”

Picking up his line of thought, I replied, “Actually, I did pray for you to come pick me up. You could say so, yes.” I opened the pristine white door to the back seat of the Mercedes-Benz and got in.

His name was Edmund. His narrative was a variation of Lenny’s from the previous day. Edmund was about eight years younger than Lenny, with a family of his own to tend to. He introduced me to the business of corporate taxi booking services, “It’s more expensive lah, but guaranteed, we are there, rain or shine, we are there!” he said with absolute conviction. He then proceeded to share an alphabetical list of long, complicated titles to his current portfolio of corporate clients, “They all like me very much, because in more than thirty years driving, not one accident.” He smiled. “Good track record right?” He looked at me from the rear view mirror. I smiled and nodded.

But Edmund’s greatest frustration was the general lack of respect Singaporeans had towards taxi drivers and their profession. Citing various internet forums and newspaper discussions around taxi services in Singapore, he thought that Singaporeans were generally an unkind and intolerable lot, “People say taxi drivers play hide and seek, peak hours don’t want to drive, go somewhere else and hide. I mean, where is the reason in that? Even if we are taxi drivers, we need to make money, we need to plan our routes strategically! So for example, if we are in the city at night on a weekday, we of course try not to pick up people and then go all the way west or east right? It’s business sense what. Because if we do that, then we have to make our way back into the city center on empty seats to pick up more people. It’s not practical. Diesel is not cheap you know.”

As Edmund rounded the corner, nearing destination, I posed the same question as I did to Lenny the day before, “What was life like when you were growing up? Do you like the Singapore then or prefer it as it is now?”

“Last time was much better.” He said in a softened tone of voice, after his previous vexations.

“Really? Why?” I queried.

“I grew up around Braddell. My family had a kampong there, with pigs and ducks. We were not rich, not rich at all. Our land was very small and the house, very small, with that kind of leaf roof you know?” his eyebrows raised in my direction, ”We had to work a lot,” he continued, ”like taking care of the farm and the animals. We had a lot of fruit trees, guava, rambutan, chiku, all that. Not modern like now, but we were happier then, more carefree life.” He paused, looking for traffic left and right, ”Simple, but carefree.” he reiterated. ”Now, life is very stress, people complain a lot, you take a road they don’t like, they complain, heavy traffic, they complain as if your fault.” He sighed, with palms pressed against the steering wheel and with eyes distant, he continued ”Now, everything modern, but I miss the kampong life, you can say lah.”

Before stepping out of the car, I shared with Edmund that while I never lived in a kampong, I understood a little about kampong living, with fruit trees in the garden. I shared with him that my parents grew up in such an environment, during a time when they could swim in rivers and play by the beach after school. Their narratives, whenever shared, contained a similar touch of nostalgia with a lacing of mischief, of a life of greater freedom, in its simplicity.